The Pastor's Heart with Dominic Steele

Christian leaders join Dominic Steele for a deep end conversation about our hearts and different aspects of Christian ministry each Tuesday afternoon.

We share personally, pastorally and professionally about how we can best fulfill Jesus' mission to save the lost and serve the saints.

The discussion is broadcast live on <a href="https://www.facebook.com/thepastorsheart">Facebook</a> then on <a href="https://www.youtube.com/@ThePastorsHeart">YouTube</a> and on our <u><b><a href="http://www.thepastorsheart.net">thepastorsheart.net</a></u></b> website and via audio podcast.

The Pastor's Heart with Dominic Steele

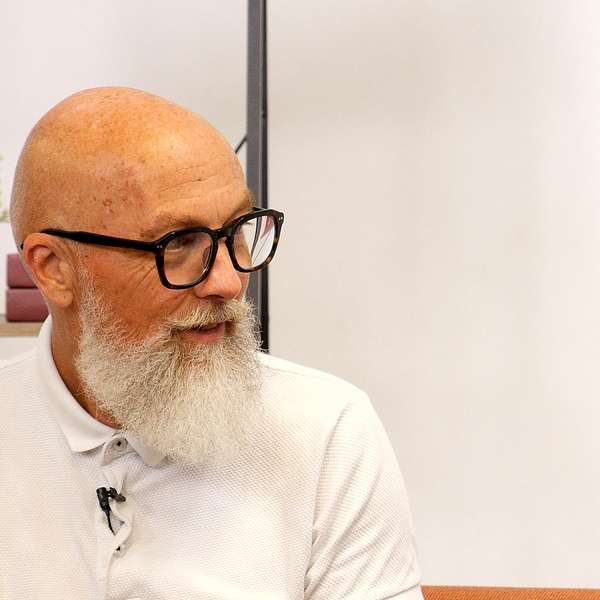

Creating a future proofed church - with Stephen McAlpine

Stephen McAlpine says the real question is “Does the future have a church?”

The statistics are not our friend.

We have been talking on The Pastor’s Heart about dropping church attendance. Stephen McAlpine is writing about the more widespread phenomenon.

He says some countries like the US are coming off a high base and in those places there is fat and cultural cachet to play with, whereas the level of religious commitment in the UK has dropped so dramatically that it is possible to imagine a time when Christianity will be a thing of the past.

In Australia the proportion of people self identifying as Christians has shrunk to 44% in 2021, down from 61% in 2011.

Church attendance across the west is collapsing with the rise of nones and dones.

Ministry Consultant Stephen McAlpine from Perth in Western Australia has a new book FUTUREPROOF.

Order online: https://wanderingbookseller.com.au/products/future-proof

Anglican Aid

To support Anglican Aid's Christmas Appeal - Click: Anglican Aid.

The Church Co

http://www.thechurchco.com is a website and app platform built specifically for churches.

Advertise on The Pastor's Heart

To advertise on The Pastor's Heart go to thepastorsheart.net/sponsor

It is the Pastors' Heart and Dominic Steele and creating a future-proof church with Stephen McAlpine. Stephen McAlpine says never mind the question does the church have a future? The real question is does the future have a church? And the statistics are not our friend. We've been talking on the Pastors' Heart about the drop in church attendance in Sydney, but Stephen McAlpine is writing about a more widespread phenomena, he says, of the drop in church attendance and religious commitment. Some countries, like the US are coming off a high base and there's fat and cultural cachet to play with, whereas the level of religious commitment in the UK has dropped so dramatically that it is possible to imagine a time when Christianity will be a thing of the past there. In Australia the population self-identifying as Christian has shrunk to 51% from 67% a decade ago. Young Christians fall away from faith at an alarming rate on entry to university and there's a real concern that we are losing a generation of young people to a program of self-fulfillment. Ministry consultant Stephen McAlpine is with us in Sydney from Perth in Western Australia. And, steve, I've just read your new book, future Proof, and at times you're speaking to pastors, but your heart is particularly for the individual Christian who is being buffeted by these cultural changes. Yes, look, I obviously want to write for pastors as well, and I think, but it's a combination. How do we work together as a church through leadership and into your people, just dealing with the anxieties that people are seeing come forward culturally in the same sense that the anxieties that the wider culture has? We also have, but we have this is what I'm writing about in Future Proof. We've got a framework to mitigate those anxieties and indeed move beyond them into a hope and also show that to the world. Which gives the scary story there of the stats.

Speaker 1:I think I wrote my first book saying well, here's where we've come from and it looks hard, but I'm writing a second book going. You know what? There's some confidence we can have going forward as well. Well, we can have confidence because we know the gates of hell will not prevail over the church. And yet I've got these statistics that say the road is going to be bumpy in the short term. Yeah, look, that's the thing I think I don't want to just go. Well, we know, we've read the back of the book and we win.

Speaker 1:We've got to say what does it look like in 2024 to be getting ready for 2054? And that's part of what my conceited in the book is. If the DeLorean car from Back to the Future arrived on your church car park and a 30-year-older version of your pastor jumps out and says quick, I want to show you what it looks like. You'd want to do that but you don't get the chance to do that. But you can see the trends of where the future is going and that's what the book's about.

Speaker 1:How do we put the money in the bank now, or start to put the money in the bank now to be a faithful, flourishing Christian community? Well, you've got to say it's madness not to be saying there's a change coming. We've gone beyond the point of saying, oh, that was just a slight breeze. You know, the wind has come in full bore. And if you think about the cultural changes that we've gone through in the last 30 years, what's acceptable to say, what's not acceptable to say? The drop-off in church attendance, the framework about how you think, about what you can know, what you can't know, meaning and purpose questions, all those things in the West seem to have come up to the surface in hot-button ways as well, not just philosophical abstract ideas at university on the ground, and that's, I think, where people are feeling discombobulated by what we're going culturally, and Christians are not immune from that, do you think? I mean, as you engage with pastors, are you finding some are saying yes, yes, yes, we've got an issue here, and some are putting their heads under rocks? Very few putting their heads under rocks, I think, these days, and I think partly because as we've aged and baby boomers are retiring and my generation, the X-generation type, in more leadership roles. We were in that crossover generation where we saw things start to happen. It's not so much where we see things happening. Do we pull the same levers as the past to make things continue? Can we expect that if we do this A, b and C in church, we'll have the same results as 30, 40 years ago?

Speaker 1:I'd say that the headwinds we're facing, the cultural headwinds, push back against that a little bit. Let's drill into the headwinds first, and here's a quote anything that restrains self-fulfillment is a threat to individual and social well-being. Hence, the default position is to assume that we belong to ourselves and that any authority that challenges this will be met with a vociferous and hostile response. And the cheap way to say that is you, do you. And that's the cultural moment we're in, that personal identity and personal identity markers are absolutely critical in our cultural moment, that I decide who I am, the expressive individualism thing and Alan Noble's book You're Not your Own talks about these issues and I know, as I'm writing about them, I'm saying how do you bring the gospel message to bear in a way that already culturally people are saying that would do violence to my personal identity? And obviously there's always issues around sexuality and gender that are primary with this identity issue, but they're not the only issues. It's that autonomous self that is a big challenge, but it's not just for what's going on out there. We imbibe that as Christians and so we come to church and we live in such a ways that we go well, you do you is my default, and then I'll figure out how to do the Christian discipleship stuff underneath that, rather than saying do I need to put you, do you? Aside at some level for the context of what it means to be part of a Christian body moving in a certain direction?

Speaker 1:Let's just analyze America for a minute, and I mean the Roe versus Wade overturning. What was your take on that? Well, it's interesting that there has been 20 or 30, 50 years of pushback from conservatives on the Roe versus Wade decision and many articles in the last 10 saying they could see a time when Roe versus Wade would be overturned by the Supreme Court. And indeed it happened. But it's interesting that even prior to that happening and just when it happened, there was a shrill sort of response from very strong progressives that somehow this was an overturn. This is going back to Gilead, you know Handmaid's Tale. I mean, that's what some have said, that it really was the Handmaid's Tale being played out in the United States. But that didn't happen. And what you noticed and more prescient progressive writers and thinkers said, the cultural tone has changed so much that, even if it's overturned by the Supreme Court, the framework of our culture will ensure that it continues in the states. And that is what's happened in the states, as it's gone from a federal issue to states to side on it. Guess what? Each state votes for abortion rights. Something's changed in the last 50 or 60 years in the in the water we're swimming in about what freedom means, what it means to do what we want to do. Now there are caveats to that, of course, but it wasn't the case that it was a return to the 1940s. It just didn't happen and it's not going to happen.

Speaker 1:You explored an issue surrounding a photograph of one woman with her a pregnant woman, eight and three-quarter months pregnant, with her belly exposed and written on her belly not a human speaking of, yeah, not yet a human. Not yet a human, yeah, do you want to reflect on that for a minute? That was a very interesting. I know right about in my book, a very interesting point at the protest against the reversal of Roe versus Wade, that someone who is obviously going to have a baby writes not yet a human. It actually kind of backfired a little bit because people everywhere. I was quite surprised because I mean, I'm thinking by eight and a half months, haven't you got emotional attachment going on and that all came up. So I think she was making a statement, but in one sense, the visual of that statement was even too confronting for those who would be progressive. Yeah, very much so, and so it's much more complicated.

Speaker 1:Where did that debate go? Well, it kind of died down a little bit, I think, because most of our ethics is driven by aesthetics these days. I think culture and we see that that beauty determines our ethics and which is why so much of our modern, you know framework of ethics is built around the beauty cult and what things look like, and so people thought that was a little bit odd. So I think, even though there's been 50 or 60 years of pushing the one narrative on this, there's something in us that recoils against that, against saying that an eight and a half month old baby is not a baby. Let's not dismiss natural law in that process, and one of the things I would say too is that Protestantism in general hasn't done very well in public square natural law conversations, perhaps as well as the Catholic Church has done, and things like that.

Speaker 1:So one of the things we're having to do is figure a way to have conversations with people around things when things like this are such hot button either or topics, and I think the average Christian I speak to really loves people, wants to see people love Jesus, but is afraid of the hard question that might get them bowled over or responded to with heat. They want to answer truthfully and lovingly, but putting those two things together in the cultural moment is hard, is part of the answer asking well, why is the case that if we've got such a high standard of living, have I got these big problems of anxiety, this tsunami of anxiety, confusion of a meaning purpose in life? No, it's. What I say to people is that all the cultural moment we're living in gives us every experience we want. This is something Mark Sayers talks about as well. But the meaning and purpose bucket, he says, is pretty empty. The people are scratching on for meaning and purpose and, in one sense, when you remove the Christian framework from underneath, you've got to replace it with something and there's a battle going on, that's to say what replaces the meaning and purpose program that the Christian framework gave the West. And that isn't just a question that Christians are asking.

Speaker 1:You can't you read Tom Holland, you read Douglas Murray, you read some of these major thinkers? They're asking, and that's why Jordan Peterson, for example, is so popular among young men. There's meaning and purpose issues going on. So I think there's a deep, not just a personal anxiety. There's lots of that and you know that's something that if you need you have that. You go and see a psychologist. But there's a cultural anxiety. We don't know where we're going. It feels like a rollercoaster. What's going on with victimhood as my mind set? That's an interesting one and I think Carl Truman talks about this in his book the Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self that the intersectionality totem, where voices that weren't heard in the past have been pushed to the surface, and voices that had it were loud, are told you've had your say.

Speaker 1:So that's why I think that churches that say, or Christian groups that say we're victims too, here we should have our voice, and they get pushed back. They got to realize that the way the framework of the culture is working at the moment, it pushes the other voices to the surface Sometimes. That's right. But also I think we live in a therapeutic culture at some level. That's not to say that all victims are just into therapy. There's true victimhood that needs to be repaired. And I think we also live in a culture that brings things to the surface through information comes to the surface much more quickly. You see, if there has been a terrible environment, it comes to the surface much more quickly. People can join the dots together. So technology is changing that. But also Carl Truman talks about the way that the voices in the past that were culturally on the edge of the culture and I brought to the surface.

Speaker 1:And that's happened culturally but it's now happening legislatively as well, and voices that maybe were at the center have been told when you had the center of power, you did things wrong. You need to take a side step a little bit and that's going to have implications for us in the church. It does have implications for us in the church. I don't think we should be too nervous about it at one level. I'm not saying I can't wait till the culture is not Christian. I think that would be a terrible thing.

Speaker 1:I've written a blog post called Two Cheers for Nominalism. You know, I think the Christian framework has been a good thing and we don't want to lose it. But the church is going to find that it's been told you've had a seat high at the table for a while. Well, move down. And you're seeing that effect more in the public intersection between the church and the state, not just simply in church. You're seeing it in Christian schools. What does legislation mean for employment? What does legislation mean for identity of your students, how they can dress, what they can be called?

Speaker 1:And if you hold to a creation view of what it means to be human as a church and that was fine 30 or 40 years ago to say that suddenly it becomes, gets on the front page of the Sydney Morning Herald or whatever newspaper in your city and suddenly you're battling against a sense that you're creating more victims by being an institution that won't let people express themselves. All of that is very discombobulating. Now you're actually helping consult Christian schools. How do you give us a little consultation here? Because we've got some principals watching. Yeah, that's true, so I'd better watch what I say. I'll be sent to the principal's office.

Speaker 1:I think what I'd be saying is the first thing is you need to understand that the average person who comes to your school who's not a Christian, from a non-Christian family, is not Christian in a different way to what people were not Christian 40 years ago, meaning that I think people 40 years ago were not Christian in a kind of Christian way the framework and now they're kind of not Christian in a way that many Christians don't understand, and questions of identity and meaning and purpose are very different. So people are sending their kids to Christian schools because they're nervous about the wider culture. They don't necessarily want the gospel roots, but they want the safety framework that a Christian school might give. And I would say to principals look, don't go in feeling shocked when kids come to you who are completely all over the place in their thinking, or when parents even do that, or even their lifestyles. You've got to then decide how do we showcase the gospel fruit in this setting? We can maintain our school's framework I think we but you have to hold your nerve a little bit when the culture comes to get you. The biggest advocates from any Christian schools are the non-Christian parents, who realize there's something different about the Christian school, but they can't put their finger on it.

Speaker 1:So I think in our future, if things get hotter for Christian organizations, the temptation is to lean back, and I think no, lean into your difference. I think the difference thing will play out well for Christian schools. That's not to say that I don't think legislation will make it harder for Christian schools. It already is, and it's, in some states of Australia, just making it harder for Christian churches to speak about issues around anthropology, for example, and I think anthropology is the big question at the moment in our culture. So Christian schools will keep going. They have to navigate that space well, and there's different types of Christian schools.

Speaker 1:I mean, if one thing is clear, well, church attendance is dropping. Enrollments in Christian schools is skyrocketing. It is, though, and it's not translating. So the question I would have to say is is there a way that the Christian school can say how do we work to help our people see that after school, when you finish school, this family could still be embedded in a Christian community? And that's the hard one. I long for the Christian school councils to really think hard about how to we promote the mission of Christ Jesus. Yes, and I think I'm not sure the family's correct, and as I look at the Christian schools around me, I'm fairly consistently disappointed. Yeah, I look, there's always going to be a battle between those. I think, for Christians in general and Christian schools.

Speaker 1:Don't be afraid to weird it up a bit as a Christian, because I think the vision of human flourishing that Christianity has and the goal of humans not just what a human is, but who a human is for is so vastly different to the secular framework at the moment, but it's almost what I call repellently attractive. It's like that seems really odd. I think a strategy of saying minimizing difference is it hasn't born good fruit, and I think it's challenging it. You'll get pushed back, but there's something about it that's attractive to people as well, the saying there's something different about you. I don't think that's a bad thing to lean into difference at all.

Speaker 1:Going forward, another thing you're suggesting we can speak with confidence about is this chronic problem in our community of loneliness. It's a massive one, and that's I'll be looking at the future. We're becoming more polarized and we are becoming more lonely, even at the same time that technology is promised to bring us together. It actually can do both pretty effectively. It drives apart, as we see in the way social media can do that. But already in Australia, one third of Australian dwellings are single person dwellings. Yeah, I live in an apartment complex of 1500 units and 70% of one bedroom and imagine saying my church is here to reach the families in the area, but 70% of the people living in your housing complex are single. Yeah, and it might feel confronting for them. You might say you don't want your church to feel like a family reunion, but someone else's family reunion all the time. So loneliness and singleness, and by choice. It's not as if everyone's looking to get married. There's a lot of choice. It's too hard, it's too complex. I don't fit. That's going to be an increasing factor and we've become a little bit atomized with the polarizing debates around various things. We always feel like we're, you know, one wrong comment away from a personal cancellation by someone.

Speaker 1:Tim Keller's last book was called Forgive, for all the great things he wrote on culture, his last book on forgiveness is a really interesting book about how you do forgiveness with people and how you navigate that space. I think we're going to becoming more lonelier and less forgiving cultural frame in the future, and the church has the opportunity to showcase something different. Help me, then, on this issue of loneliness. I mean, if 70% live alone, what strategy should we be adopting? Well, befriending people isn't a bad idea, is it? I think one of the things I was writing about in my book is if you've got people coming to your church who aren't in family units, what does it look like to just simply broaden your table and I literally mean your table that you can operate as a family unit? If you have a family unit with single people there, with divorced people there, with widowed people there, with people who don't fit the narrative of what a successful person is, and you can model that to each other and to the next generation growing up? Because I know we like to be with people we like to be with. But somehow the gospel says that's not quite what this is about and I've seen churches doing it well, where they lean into helping the lonely people.

Speaker 1:You talked about a plus one within your church. I thought that was a lovely idea. Yeah, look back in Perth our church had that idea of every semester you do a plus one thing. So we're not trying to make you ninja Christians where you've got to change everything up all the time. We recognize people are busy and have other commitments. But if you plus one with a meal together once a month with a group of people diverse from your church who you normally wouldn't get together with and who might be on the fringe just once a month, and if enough people did that in your church with a plus one every month, it would start to just. The wheels would start to turn a little bit. It would lose the inertia of that and that's where you can invite someone else in who's perhaps not Christian and it's not a bait and switch. Now we're going to have a big Bible study. It's just a meal together so that people can observe what people in community live like.

Speaker 1:You can imagine if 30% of households are single dwelling and that goes up, people won't see what long term relationship looks like when you have to forgive someone or when you have to put up with someone's foibles or something like that. And we want to be able to do that as a body because of what we believe that God has done in bringing us together as the temple, living stones brought together, body parts working together. Both are the analogies in the scripture. I'm just thinking about loneliness and forgiveness. But you were also saying, I think, that our community life as a society is fragmented. It is Sporting clubs, volunteer associations, men's sheds, all those kind of things on the way down, not just churches.

Speaker 1:No, I mean churches going well. The discipleship program isn't working because people aren't volunteering. That's across the board. But even though I was reading in the paper today, there was one about attendance at school that we were tracking on at 80% before COVID and it's armoured and what you're seeing is there's a sense in which social anxiety has kicked in a big way. There's also a sense that people still get together, but they're far more tribal about it now. So what we're seeing is there's much about hotter groups, where you don't have people in your group who think differently to you.

Speaker 1:So the churches in one sense, a group of people that are they're maintaining the unity of the spirit and the bond of peace. They're not attaining it. They're maintaining what God has given them. So the church should look like a bunch of people that would have no right to be together for any other reason but for Jesus. And what you're seeing in other organisations and I see it as this you thin out the depth of your relationships.

Speaker 1:I do park run from time to time. You know the 5K run. It feels like church without Jesus. But if you fell out with someone at park run, there's no. Well, here's the forgiveness way to get back in you just go to another park run and forbid it that we would ever just up and leave a church and go down the church. But if that's a sadness, isn't it? And that's what we've got to learn how do we figure those things out? And that you know that's part of the issue.

Speaker 1:But for me it's saying, culturally, we're atomising and technology allows us to do that, and then people are spending more time at home and all those things are all happening at the same time. And when you pull the lever, if I need some help, it's usually you only got the government left, and that's partly the problem, I think. How do we outlast the culture? It's interesting that one of the things we picture that Christianity is it gives you a better life now. But the point of the Gospel is that we have life in the age to come and it's the hope of the Gospel that one day this body will be raised and a new creation will come about. So I don't need everything I want now, because it's not where my hope lies. And the way you can outlast it is to be so committed to the goal of where God is bringing the new creation and Jesus' return that you go. I don't need to play this out my way all of the time. I can live in deep, meaningful ways that aren't just about this age and that will over time, I think, shape Christians differently to how people who don't have that hope are built. It means that the people who retire in church aren't going well. I've done my bit. It's entitlement day now. I'll see you in 20 years time after I've done seven laps around Australia. It means how do we serve now that we have more time and we don't see those incremental bits.

Speaker 1:And I want to commend the church here that when I meet people who are not Christian and have no Christian background, their first response when they see Christians operating like that is Bermusement and almost envy. In fact, one of them used that word to me I envy you Christians. I said, why do you envy us Christians? She said, I see how you related to each other during COVID. It was very different to my people and she goes yes, it was just different. And she was a lapstar-ish Catholic and there's no one as anti-Christian as a lapstar-ish Catholic. But she envied something. Well, that's true, and that's part of the outlasting the culture bit, because I wouldn't want us to have just a life for this age. The future proof really is that there's a future coming. That's glorious and I don't need it all now and I can serve others richly and deeply and at cost to myself, because God is no person's debtor that comes back. In that sense, the age to come will fulfill all those things.

Speaker 1:What should our engagement in politics be then? What is it, or what it should be? That's an interesting question. I've just been reading Aaron Wren's book Living in a Negative World, and Aaron Wren talks about he would like to see more Orthodox Christians leaning into the political space. It's going to be hard, but he thinks that they have got something to say to the cultural moment. How you do that, christianly lobbying, seems to me a little bit 2010. I think the parliament itself feels sort of sealed against the Christian public frame. But I think Christians should be involved in politics and we know Christians who are. But how you think it's going to swing around to the Christian framework again, perhaps, or their Christianized easy way, an easier way of dealing with life as a Christian from politics, I'm not sure that's going to happen. But I want people to be in the public square and we have to get up to speed, I think, with a good way of speaking about difficult ethical issues, a good way of speaking about the direction of politics and the future of the nation, a good way of looking at what does a Christian think about, how we do community life together in lonely suburbs, all those sorts of things.

Speaker 1:I mean, you spoke about writing to a journalist and you wrote a thoughtful letter disagreeing with them, and yet they appreciated, actually, both the kindness in the tone as well as the thoughtful engagement with their thoughts and that's yeah, I did that and I remember her writing back thanking me for saying something in a way that, even though I disagreed with her, it was kind and this isn't a bad option at times, but usually if you disagree with someone, you come out hot, and that's what you expect as a journalist from a letter and I said I disagree with you on these things, but I can see why you hold those things. Part of what I think we need to go going forward is saying here's someone's belief system. We should do this anyway. But what's the iceberg under that tip? What's going on there? And start to probe and ask questions of people. Why do you think that? Have you thought about that? Because I feel like the cultural moment is pushing us to extremes and I want us to hold firm on what we believe, but I want us to do so in such a way that we can honour someone we disagree with.

Speaker 1:It's very hard in our social media age to honour the people we disagree with. Yeah, I mean, I was reflecting, as I was reading that, on my relationship with my local MP and I was watching her the other day in a debate and I thought she actually, in terms of the manner in which she conducted herself, I thought she just did a really good job and I thought I must write to her, I mean, and just tell her that I watched an hour of the council debate and I thought she was good in this area and I was particularly reflecting on the line in Paul and seeking peace, and I think it won't make any difference in terms of this month's issues, but it'll be a little deposit in the bank in terms of our long-term relationship. Yeah, and I think that's critical, that we build up that credibility in the bank, even if people say I don't agree with what they think. But gee, there's something about the way they operate that I don't find anywhere else, and I think that's because of the hope we have. We're not looking for the approval of human beings. We're looking on the last day. We want to hear a well-done, good and faithful servant. But, as someone else has said, if God is big in our lives, then other humans aren't too big so that we're not scared of them, but they're also not too small so that we despise them. If God's big in our lives, other humans are the right size, human size, just like us, with all the foibles and weaknesses that we have and the fact that we are mortal, and we need to relate to them that way, with honour. And it's very easy to find biblical justification to dishonour people who you disagree with, and you don't have to go to YouTube for that. And I think that's part of our issue is that the technology stuff that we do, that we filter everything through, allows us to push ourselves in polarising directions and encourages that at one level.

Speaker 1:Now I've just moved into this apartment block. We've just downsized and we're talking about apartment therapy. Well, I've watched the Department of Therapy. If you watch it on YouTube, it's quite funny, it's quite good. But I enjoy the sort of people crafting their apartments.

Speaker 1:But what I noticed very much was this especially in Brooklyn and all those places, people are very content to say I live alone, I craft my life my way. Perhaps I've got a dog, but that's about it. Not that everyone's living alone and that's a certain city, but it felt like I don't need other people close to me. This is my life. I carve it out this way and I collect around myself the things and objects that justify who I am and what I do. And I often wonder what will that be like when you're 80 and you're ill and you're impossible and you make decision after decision to do it my way. Yes, and we haven't borne that fruit just yet because we're still we're in a crossover.

Speaker 1:My own father died in an aged care facility seven years ago and it was telling, and my brother pointed it out, that the people who look after Westerners aren't Westerners. They're people from other cultures that honour age and honour community a little better, and there were people in there that never got visited by anyone for seven years. And what will that be like when we're even thinner in terms of community? And what would it be like for the church to honour its old people well into the future? Stanley Harivas said that if in 100 years time, christians other people that don't kill are young and don't kill are old will be doing well unless 100 years time. Read the laws around euthanasia in Canada, for example and non-Christian secularists like Tom Holland are pointing it out that the generation 18 to 34, the number of people who approve that you should be able to access euthanasia for homelessness or depression is over 50%. Now you extrapolate that out to when the 18 to 34s are running the place and you're going to have a brutal culture In fact, with money going down and housing going down. Even in Canada they found people encouraging other people to have euthanasia, to take pressure of health bills, to take pressure of housing.

Speaker 1:If that's not a signal that there's a meaning and purpose problem in our culture, in our Western post-Christian culture, I don't know what is. I was horrified at Christmas Day discussion at much my wider family, how many of my nieces and nephews, had just bought the euthanasia. Yeah, and that's about a lack of hope and a sense of I will find control in an increasingly uncontrollable world. So there's a vague sense of comfort to euthanasia. If you think I have no destiny beyond the grave and I've got no control over the terrible things that are happening in the world, whether that's climate, whether that's war, whether it's all these anxiety or all these homelessness or poverty, all these things. That's what happens to a culture that runs out of hope.

Speaker 1:So, last word, what do you want us as pastors to do? Yeah, not panic. To be honest, this is the counter-intuitive thing. I want us to preach the big picture of where God's taking history. I think some preaching not all preaching in the past has said well, the 70s and 80s had a lot of crazy stuff about end times. Let's not even go there. But unless we as God's people are saying there is hope beyond the grave and God is going to bring about a new creation and give us a bodily resurrection where our hope and our joy will be fanned and the presence of God forever. We're not preaching the Bible. Well, there's so much end stress in the Bible as to where this thing's going and we don't lean into that enough. And I would say, if you want to prepare your people for Monday to Friday, tell them about the age to come and I think that will bleed back into how and give them a future-proof life going forward.

Speaker 1:Stephen McAlpine has been my guest on the Pastor's Heart. He's just released the book Future Proofing the Church and we will link to that book in the show notes and you can check him out at his blog, which he's also linked to in the show notes. This has been Dominic Steele. You've been watching the Pastor's Heart. We'll look forward to your company next Tuesday afternoon.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.